The concept of "Nucleus Living" aims to maximize the efficiency of residential construction by eliminating both unused and missing spaces, thereby achieving a high level of housing sufficiency. Given the latent, underutilized space reserves within existing housing stock, integrating nucleus living into these structures appears to be a logical solution. This paper examines four representative buildings from three distinct periods, presenting an overview of the types and scales of the necessary transformations in a schematic manner. Concurrently, three fundamental structural transformation strategies are introduced and implemented. These strategies adhere to the principle of minimizing structural intervention in the existing buildings. The common thread linking these strategies is the creation of corridors within the existing structures.

In response to the current housing shortage and the need to transform construction practices [1] , three central approaches have been identified that are influential without being mutually exclusive: prioritizing adaptive reuse over constructing new buildings, using replacement construction to increase density in existing urban areas, and improving space efficiency and flexibility in residential designs and floor plans.

This research outline is based on three main hypotheses:

- Replacement construction should be minimized to avoid the loss of embodied energy and other negative environmental impacts.

- Combining space efficiency with adaptability should be achievable for all residents, allowing living units to expand or contract without raising the average per capita space consumption. [2]

- Adaptability should be feasible in existing buildings with minimal modification efforts.

For hypothesis 2, this outline builds on the "nucleus living" [3] concept, which the authors have further developed. For Hypothesis 3, we examine four buildings from three different eras, each representing distinct typologies. These examples were selected to effectively illustrate key concepts. While they are not statistically representative, they are not isolated cases either, suggesting potential for broader applicability, though this is not comprehensively analyzed here.

Furthermore, this preliminary study does not provide detailed conversion plans in realistic depth but focuses on floor plan adjustments to show the basic potential for reprogramming with minimal intervention in existing buildings. Considerations such as adapting existing infrastructure and potential upgrades in energy systems, building services, or ventilation are recognized but not thoroughly explored in this study, although a basic feasibility check has been conducted.

Hypothesis 1 is not directly examined here. However, identifying feasible approaches for hypotheses 2 and 3 is expected to offer new insights into the relevance and feasibility of hypothesis 1.

Several arguments are often presented to justify the prevalent practice of replacement construction as a development strategy, designed to downplay the developers' primary economic interests:

- New buildings are more environmentally friendly due to their lower operational energy consumption, thus contributing significantly to the sustainable transformation of the building sector. [4]

However, demolishing existing structures generates large quantities of materials that are not fully recyclable, while constructing new buildings requires substantial amounts of embodied energy. These factors must be considered in this argument. Current construction practices, which prevent the separation of individual components based on their life expectancy or their targeted replacement and maintenance, further challenge this claim. [5] - Replacement buildings provide more living space, mitigating the housing shortage in urban areas.

While replacement construction often results in additional living space, new buildings tend to feature relatively larger units, increasing the space utilized per resident. [6] In practice, these larger flats do not necessarily house a proportionate number of additional residents compared to the original structures, thus offering only limited relief to the housing shortage. Moreover, replacement projects frequently result in the loss of small, efficient, and affordable units, contributing to neighborhood gentrification or the displacement of vulnerable populations. [7] Alternatively, the available space on a property could often be maximized through projects that integrate existing buildings, adhering to the principle of preservation-oriented densification. - Tenants affected by replacement construction are offered various support measures as part of comprehensive assistance plans. These include personalized consultations, offers for suitable alternative housing, reduced notice periods, and priority access to rental units in new developments.

In practice, support often amounts to simply offering residents a unit in a new development. If residents cannot afford the higher rent, they may be displaced to other parts of the city, disrupting existing community ties. Even when developers set new-build rents at cost, as cooperatives might, these units are typically more expensive due to increased overall square footage, even with the same number of rooms. [8] - Existing floor plans are outdated, reflecting an obsolete model of family living, and no longer accommodate the space requirements of modern tenants.

To create adaptable housing in existing buildings that accommodates diverse and evolving family configurations, innovative restructuring strategies are essential. Conversely, the lack of such strategies has been cited as a sociological argument against retaining the current housing stock. Developing viable solutions could be a lever in addressing these concerns.

To further diminish the necessity for new construction and replacement projects, it is crucial to redistribute existing living spaces and make use of invisible or underutilized areas. [9] Many housing associations face significant misallocation rates [10] within their current properties, where rigid floor plans often hinder adaptation to evolving needs. Thus, integrating innovative programmatic and organizational concepts into existing housing becomes highly pertinent. This approach can unlock the potential of existing spaces and mitigate misallocation issues. Enhancing the flexibility of floor plans is essential in this context. As a preliminary step, the authors have examined and developed a new living model that offers a high degree of adaptability in the "Nucleus Living" study. [11]

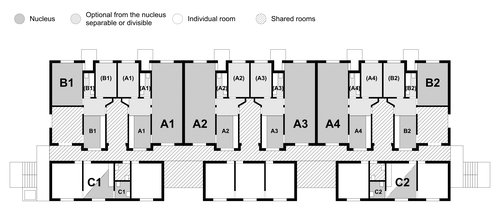

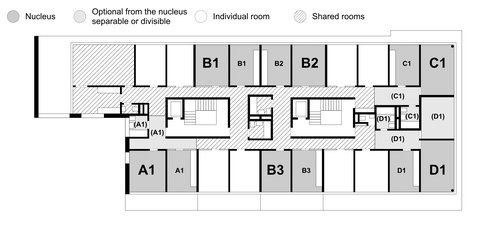

To assess the applicability of the housing forms and typologies [12] developed through this research, specific buildings from various construction periods were selected to evaluate their transformation potential. These buildings vary significantly in structure due to factors such as location, construction era, building methods, and the client or developer, requiring distinct transformation scenarios. The primary objective is to enhance flexibility to a significant degree while minimizing efforts and interventions in the existing structure. For the scenarios outlined below, we evaluated their applicability to the chosen existing buildings, outlining possibilities where feasible. Among these, Scenario 1 was consistently prioritized to align with the goal of minimal intervention in the existing structure. However, its applicability could not be confirmed for all buildings examined.

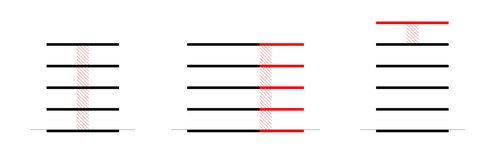

- Central Corridor Typology

In this scenario, an existing central corridor is extended to run through all flats, serving as a hub to connect and switch individual rooms.

Requirements: The central corridor must be structurally integrated, and both the stair landing and the central corridor must function independently. - Add-On Layer

The add-on layer must fulfill all functional requirements, including providing accessibility and the space needed to connect and switch individual rooms. This layer should also have the capacity to incorporate supplementary spaces to maintain the balance between private rooms and communal cores.

Requirements: Internal modifications, such as a central corridor, are structurally unfeasible. The buildings must be standalone, and zoning laws must permit lateral expansion. - Adding Stories

The addition of new floors must be considered in harmony with the existing ones. The floor plans in these new levels are designed to offer a diverse and flexible range of housing options. By implementing an operational concept that encourages easy and incentivized flat swapping, flexibility for the entire building can be ensured. [13]

Requirements: Internal modifications, such as a central corridor, are structurally unfeasible. The buildings must have sufficient structural capacity to support additional floors, and building codes must permit vertical expansion.

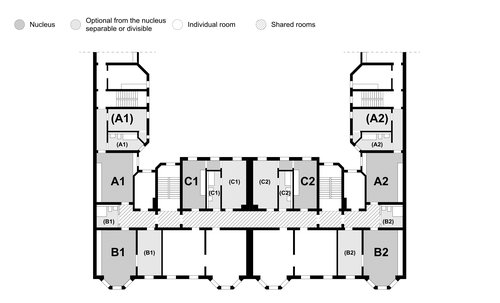

These transformed floor plans necessitate a new conceptual approach to lats and living arrangements. Thanks to the increased flexibility, these plans should be adaptable and capable of evolving over time. The examples provided below illustrate just a few potential variations among many possible alternatives. The analysis largely excluded the topic of shared rooms and private workspaces, as incorporating these areas would require an additional level of analysis. Nonetheless, incorporating this dimension could be a valuable avenue for further research.

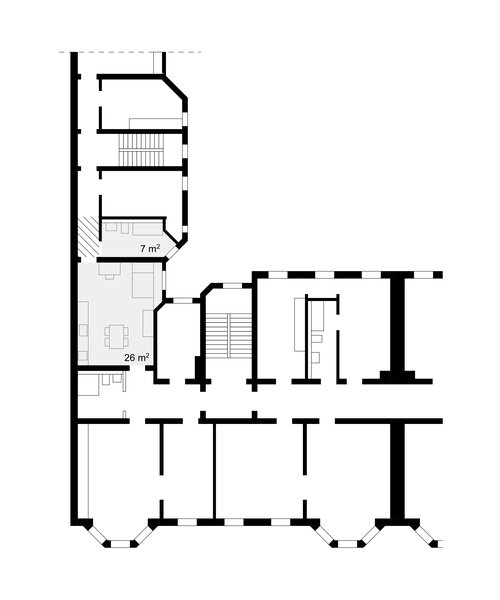

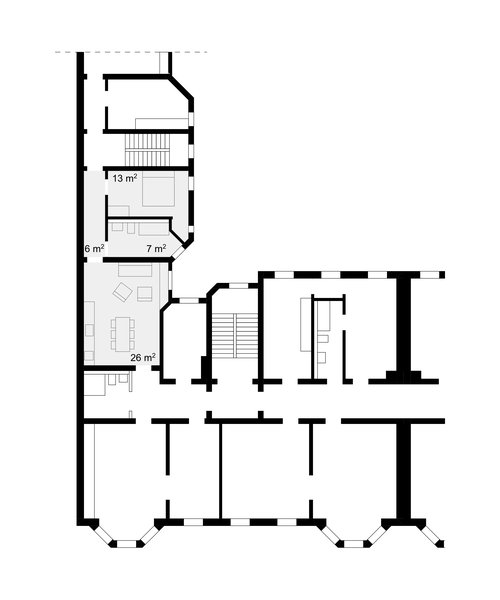

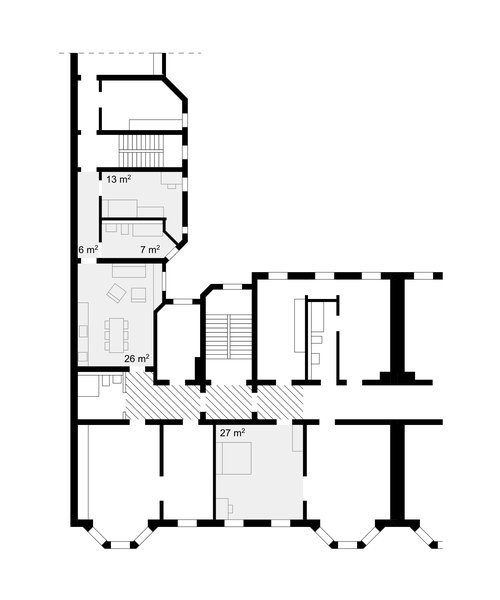

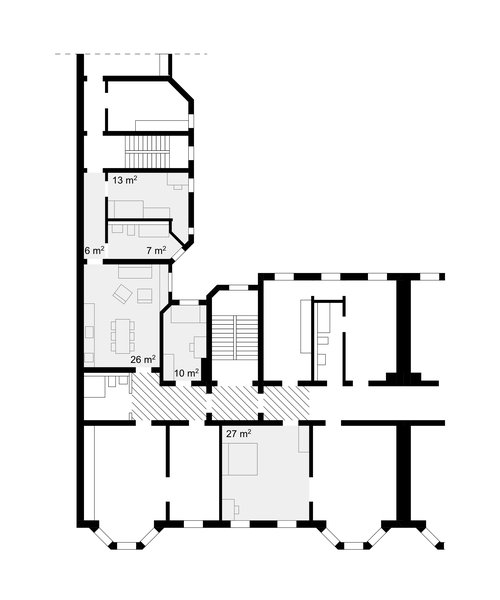

Constructed during a period of housing scarcity, the Goldacker development needed to be built swiftly, cost-effectively, resource-efficiently, and with minimal space usage in a serial manner. The flats are uniformly small and similar in layout. Since the buildings have been owned by a cooperative since their construction, flat turnover is typically infrequent. [14] The rental regulations, which are quite lenient regarding misallocation, contribute to this low turnover rate.

When re-letting, the occupancy standard is applied: the number of rooms should equal the number of occupants, plus or minus one. Under-occupancy has become prevalent due to low resident turnover, driven by the precarious housing market, lifetime tenancies offered by the cooperative, and lenient tenancy regulations.

The floor plans' space-efficient design results in low per capita space consumption despite under-occupancy. Nevertheless, these flats are now deemed outdated and too small, placing them at risk for demolition and replacement. The primary objective of intervention is to enlarge and diversify the flats while creating additional living space. This transformation will result in larger family-sized or shared flats and introduce smaller one- to two-room units. Peripheral areas will be repurposed for communal and flexible use, accommodating activities like meetings, parties, and DIY projects, reducing the "gray rooms" [15] within flats. Consequently, this can help reduce under-occupancy.

The lack of structural reserves and the low sound and thermal insulation standards from the time of construction complicate the renovation efforts and render certain strategies, such as adding floors, infeasible. However, viable solutions can still be achieved using the strategy of adding a layer.

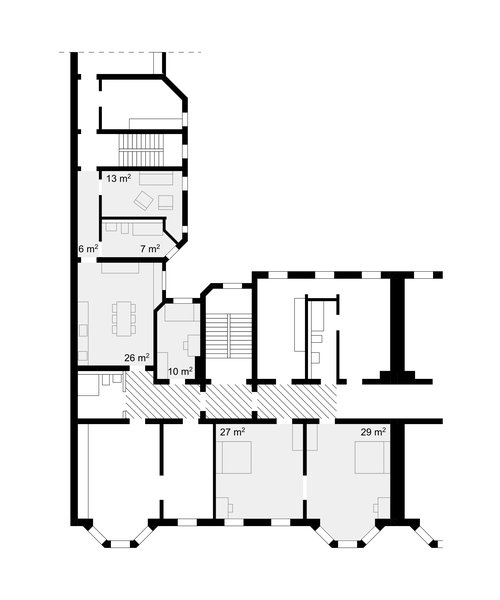

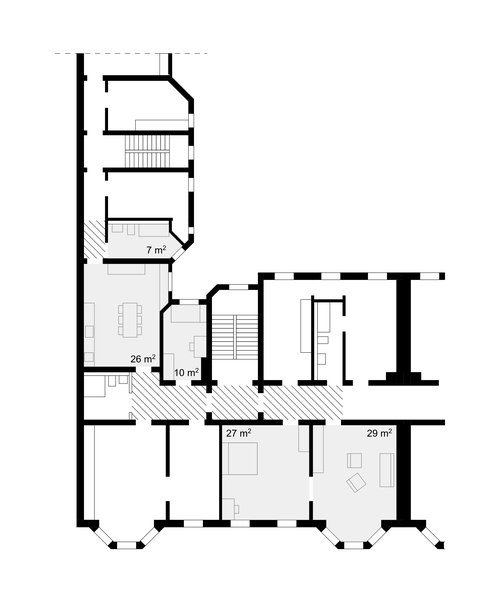

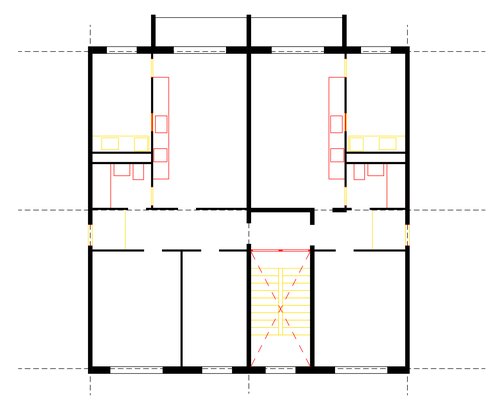

The two buildings at Rathenowerstraße 21 and 22 are examples of perimeter block developments with inner courtyards from the turn of the century in Berlin. Many buildings from this period follow a similar typology and structure, although the floor plans and number of flats may vary across floors. [16] Numerous flats have also been merged, divided and restructured over time. For the following analysis, the originally planned and realised structural condition of a standard floor is assumed: in a mirrored design, each front building has two large flats, each with a representative and a functional part per main staircase. A secondary staircase also provides access to the functional part of a flat in the front building and another small flat in the rear building.

The original, very hierarchical residential concept, which can be assumed to be the basis for this floor plan layout, can no longer be considered relevant today. Therefore, a mixed scenario with shared flats and family living arrangements serves as a (hypothetical) assumption for the current occupancy of the existing floor plans. This means that the occupancy is already assumed to be comparatively efficient, compared to an equally plausible occupancy of only 2-3 people per flat.

The perimeter block typology of Berlin offers considerable potential for structural and programmatic flexibility, a trait that has been leveraged several times to adapt to evolving residential and commercial needs since the early 1900s. However, the current housing market has resulted in a stagnation of flat turnover, crucial for this flexibility, which in turn exacerbates under-occupancy. [17] The primary aim of the intervention is to address both the under-occupancy issue and the problem of oversized flats, which are suitable for shared living arrangements but not for smaller setups, by increasing the flexibility of the flats.

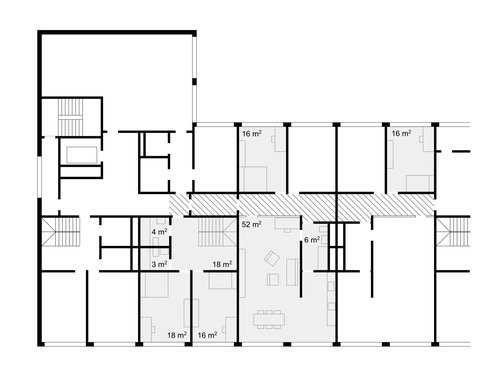

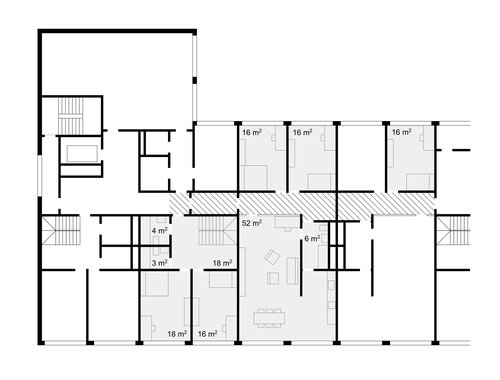

With minimal modification, the existing central corridor can be extended across and even beyond the entire building width. In conjunction with the additional kitchens and two barrier-free bathrooms at the ends of the corridors, which can be built as required, this creates an extremely flexible floor plan. The central corridor would become a communal and communicative space.

However, small-scale ownership structures and the regulations of the German Condominium Act (Wohnungseigentumsgesetz - WEG) present challenges. While extending the central corridor beyond the building boundary would be technically straightforward, building regulations related to fire safety make this solution legally challenging. In addition, extending the corridor would provide access to another emergency staircase.

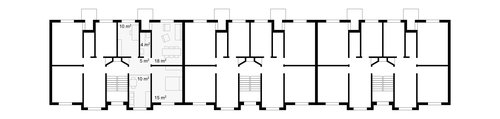

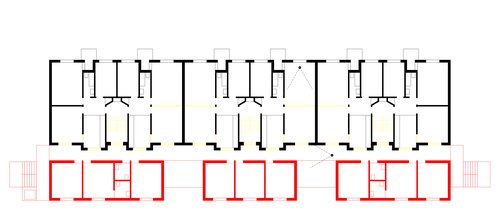

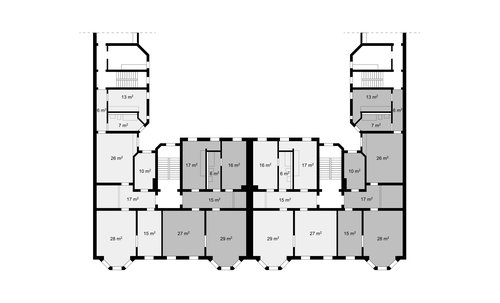

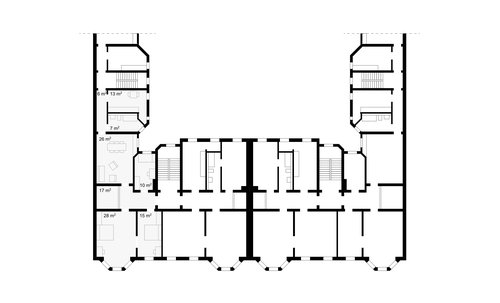

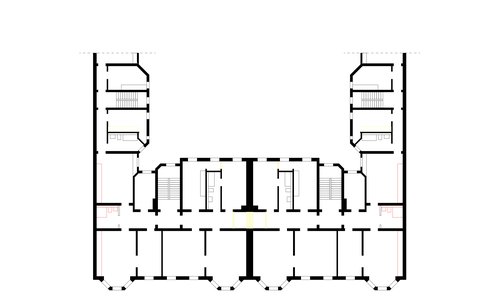

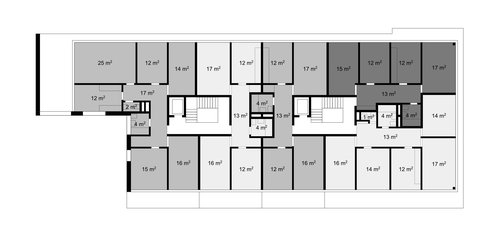

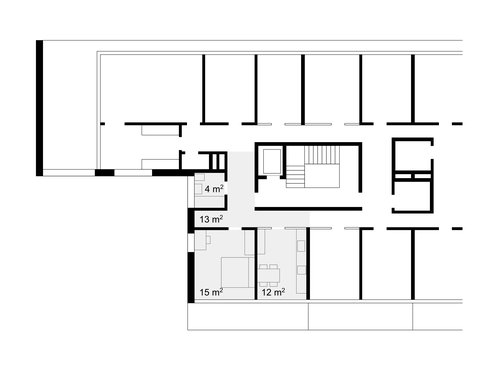

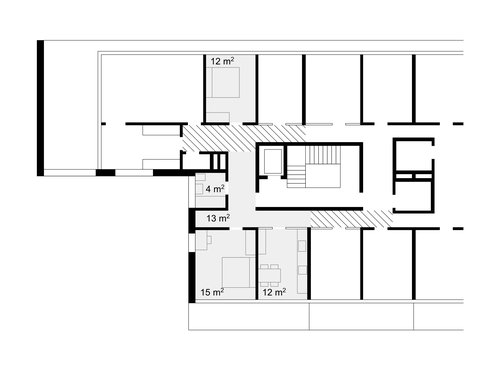

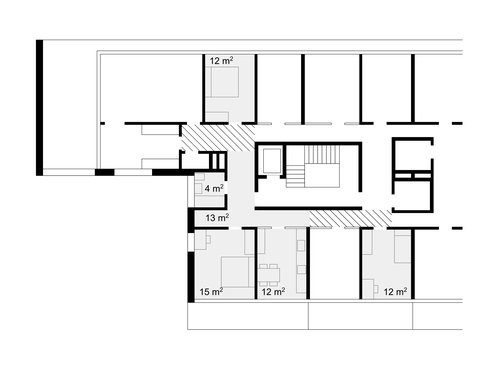

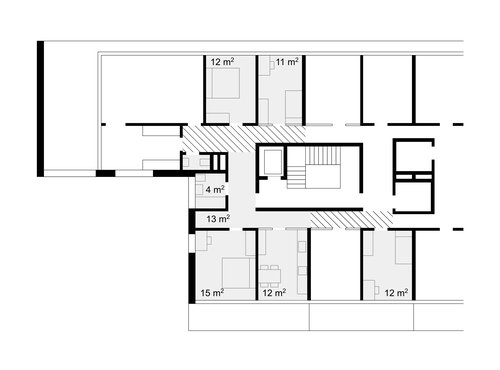

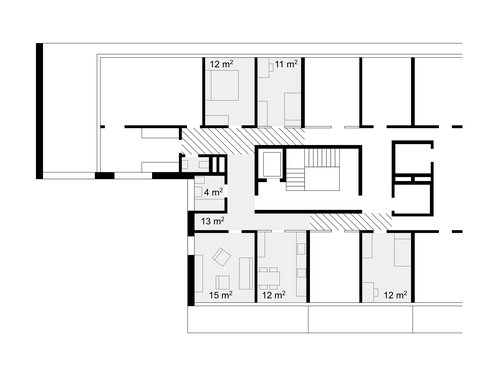

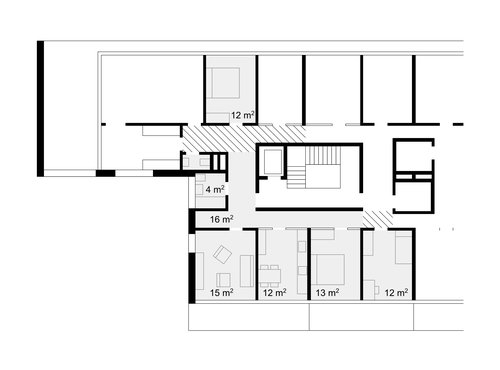

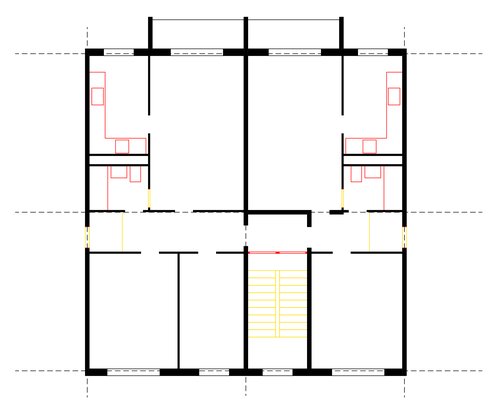

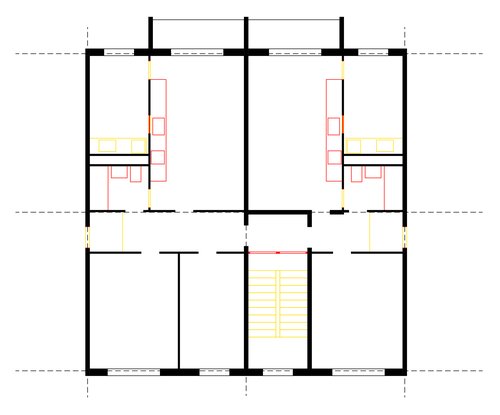

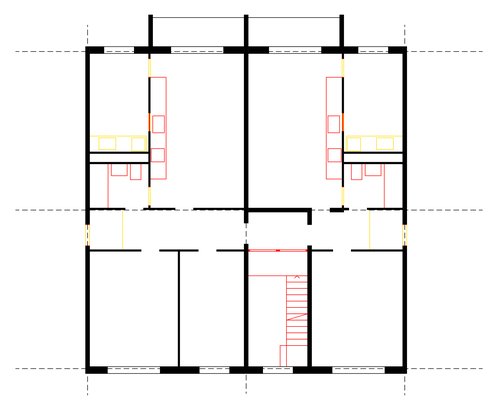

The residential building on Müllheimerstrasse in Basel replaces a 1940s structure. Situated within a fragmentary block perimeter development, it serves as the final link in a row of buildings. Executed to a moderate standard and catering to families, the building is organized as a two- or three-family house with two staircases. Two entrance halls lead from the street to naturally lit interior staircases. The rooms, ranging in size from 12–13 m² and 16–17 m², are arranged in a ring around internal core areas (with bathrooms and staircase), allowing for different levels of habitability and occupancy of the floor plans. However, depending on whether the kitchen-diner (12 m²) is counted as an additional half room or not, the flats are rather small. A 3.5–room flat or, without counting the kitchen-diner, a 3–room flat measures around 74 m², but in the most crowded case could even be occupied by up to 4 people.

With minor modifications to the building’s central zones, new floor plan typologies can be introduced, resembling layouts commonly found in office or laboratory buildings (the so-called "Dreibund" typology). This approach provides a high degree of flexibility. Additionally, the central zones could be temporarily assigned to individual flats, enabling re-individualization. The design allows for flexibility in defining the boundary between private and communal spaces. For example, spaces can be adapted to provide greater privacy and clearer separation of flats. This arrangement supports more individualized or conservative forms of nuclear living. At the same time, a large communal room (25 m²) with an attached communal kitchen (12 m²) in the south, created from the complex corridor layout, provides a kind of breathing space for the apartments, which are now generally very small but equivalent in size, with only 12-13 m². Overall, the transformation results in rather small living spaces in the occupancy variants shown. However, the plausibility can be justifiably questioned due to the fact that certain passage widths fall short of conventional standards. [18] As an experiment for minimal living spaces [19] or as a purely typological model, however, it can be classified as interesting in principle, even if in this case approx. 20% more space is required.

However, due to the era of the building’s construction, technical constraints limit certain modifications. These include potential underfloor heating routes [20] , placement and arrangement of electrical sub-panels, and ventilation ducting.

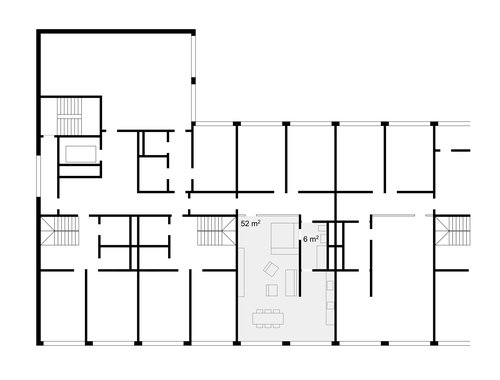

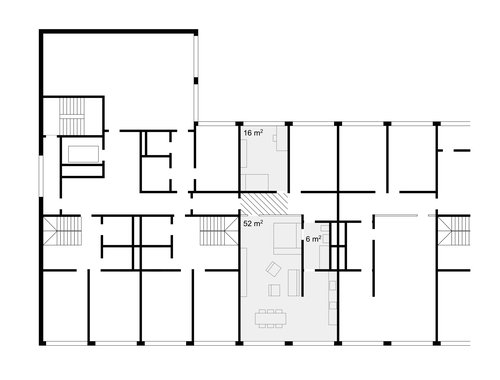

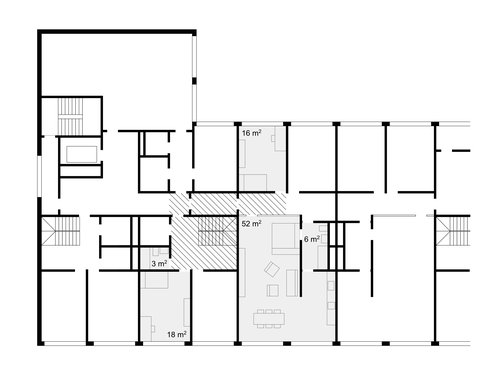

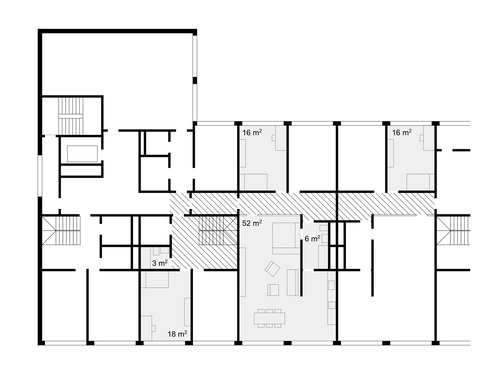

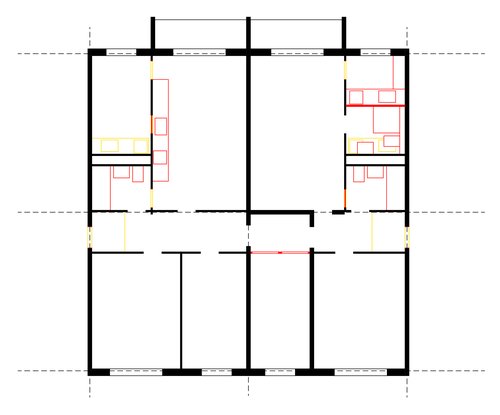

The residential building on Parkkolonnaden in Berlin belongs clearly to the luxury segment of housing. At nine stories, the building is likely classified as a high-rise according to building regulations. Its floor plan reflects this classification, incorporating generous access spaces, presumably required for fire safety, such as external access to stairwells via open loggias that substitute for enclosed fireproof stairwells. The spacious, well-structured flats include some maisonettes, all of which have direct access to a stairwell on each floor. Particularly notable are the large living areas with open kitchens, leading to a high per capita consumption of living space.

The building's structure allows for significant functional and spatial flexibility with minimal to moderate modifications to the floor plans. By introducing a central corridor, the proposed nuclei can freely access room clusters on the opposite side of the corridor. This setup enables a high degree of flexibility. A mix of different living arrangements, such as nucleus living, cluster living, student housing, or a boarding house format, is quite feasible within the existing structure with only slight modifications. This is made possible by the ability to rent out individual rooms separately while also defining spacious shared kitchens and bathrooms."

Moreover, the introduction of a central corridor could enhance the building’s escape route options, granting two independent escape paths from each flat. This improvement could also mitigate fire safety challenges that may arise during the conversion process.

As with the residential building on Müllheimerstrasse, technical constraints – such as fire safety requirements and possibly property law restrictions—pose challenges. Market-specific considerations, particularly the luxury segment, may also limit the scope of transformation. Furthermore, adapting the new central corridor would necessitate relocating two bathrooms per floor or converting the existing adjacent separate toilets into bathrooms. Fortunately, the existing utility shafts would remain unaffected by these changes.

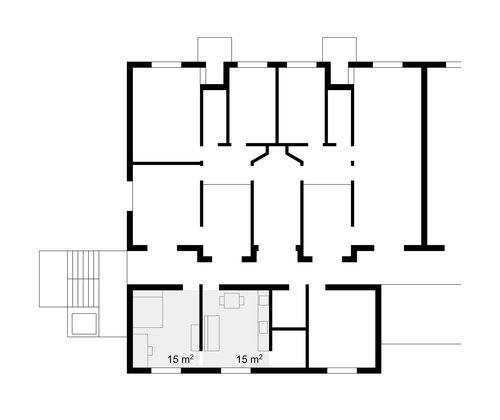

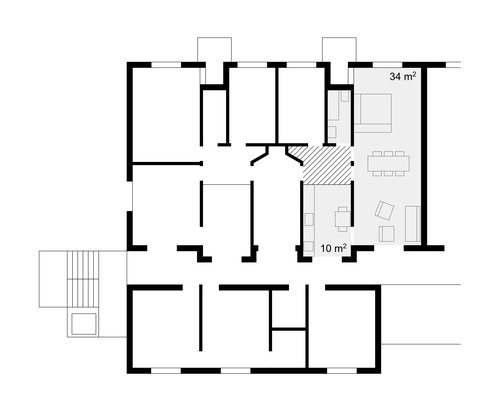

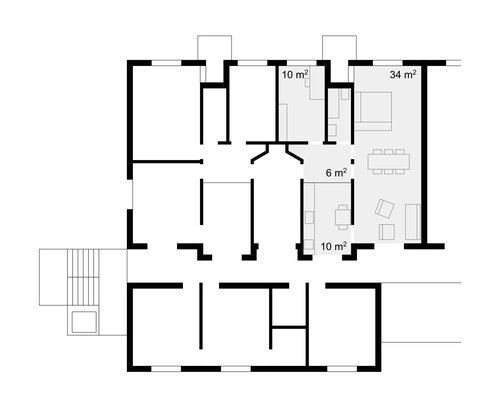

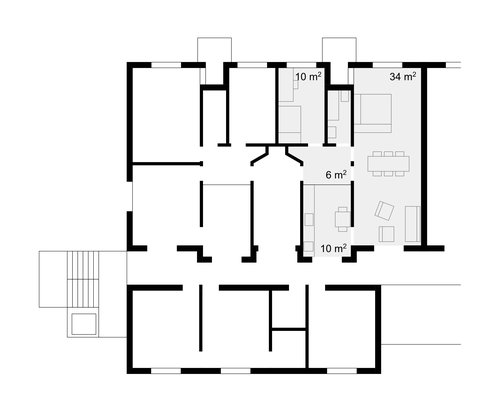

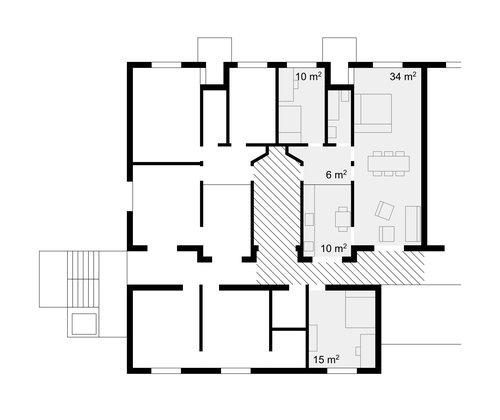

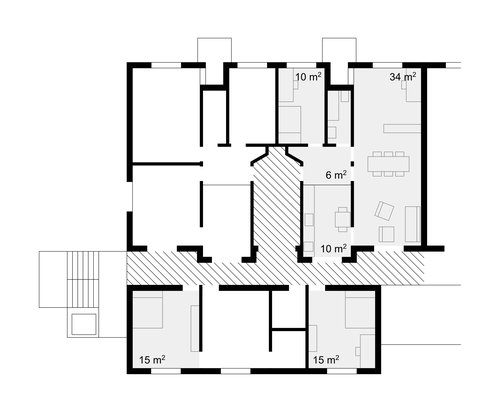

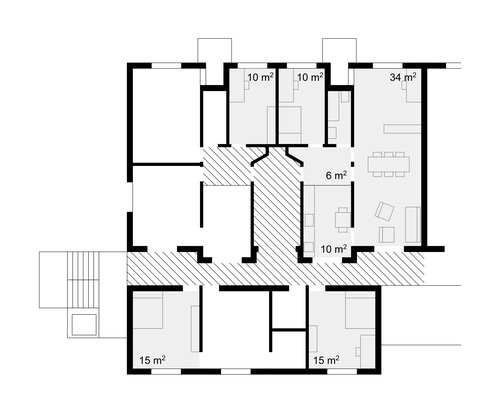

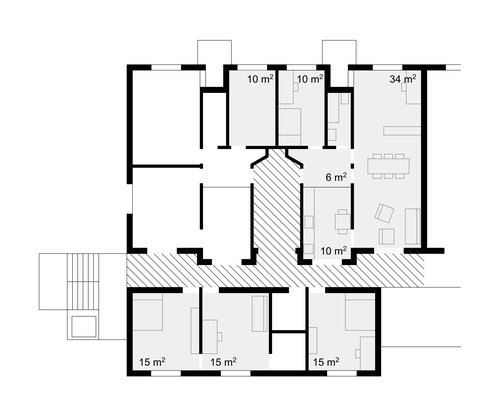

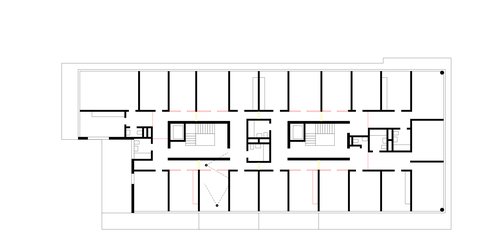

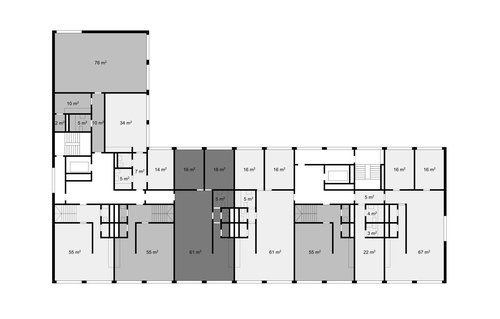

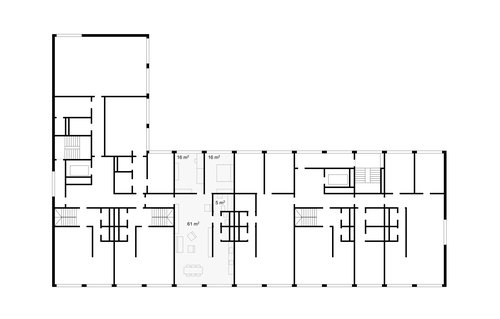

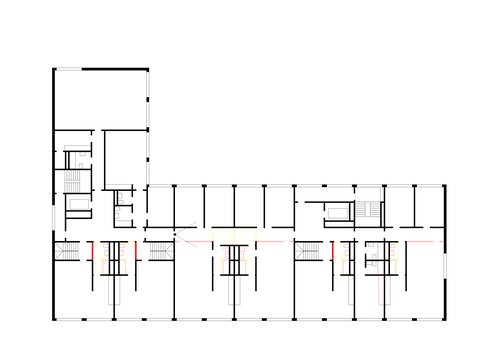

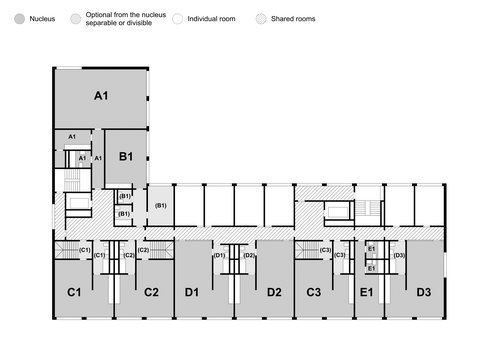

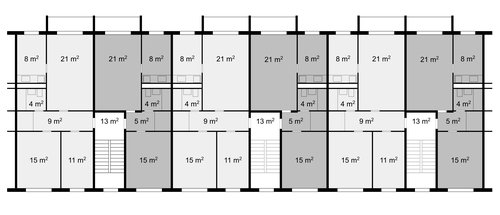

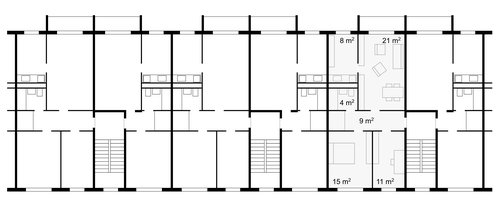

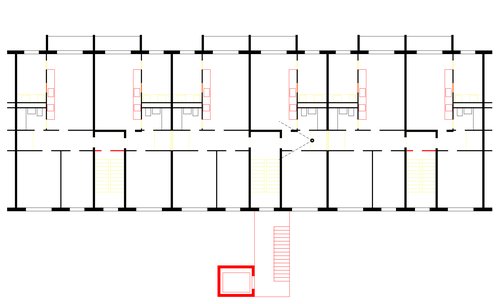

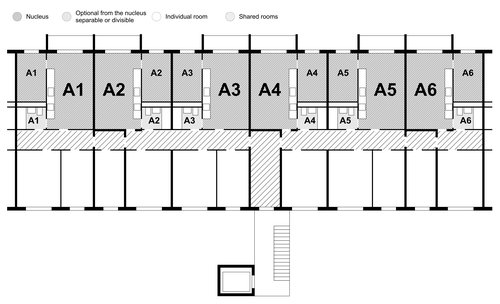

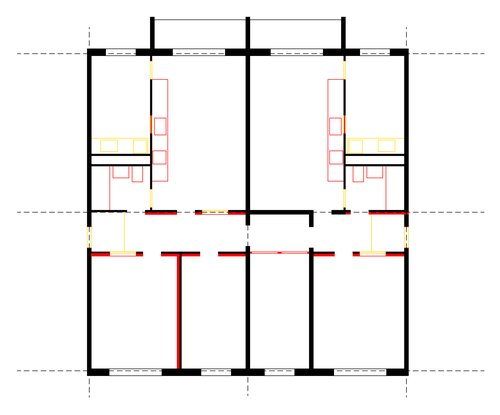

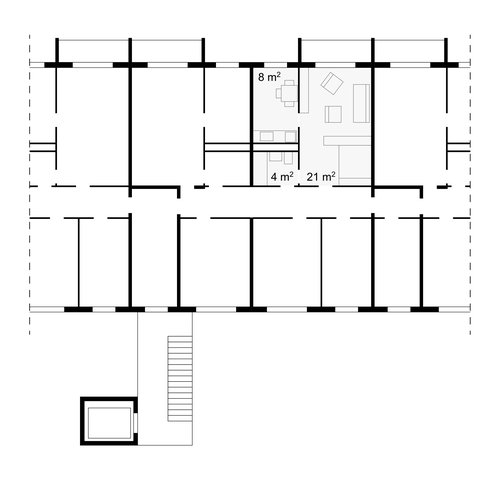

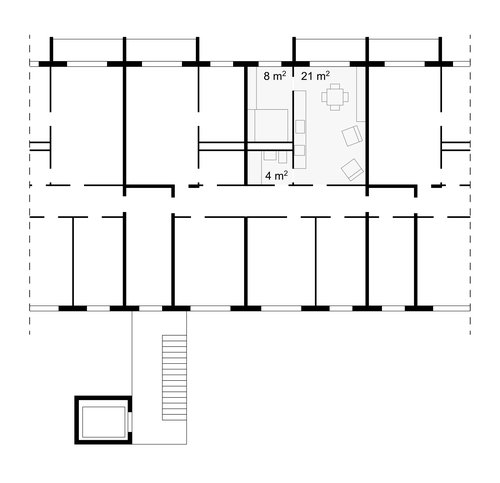

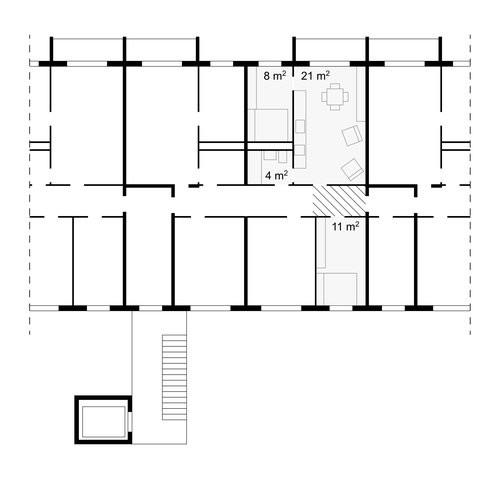

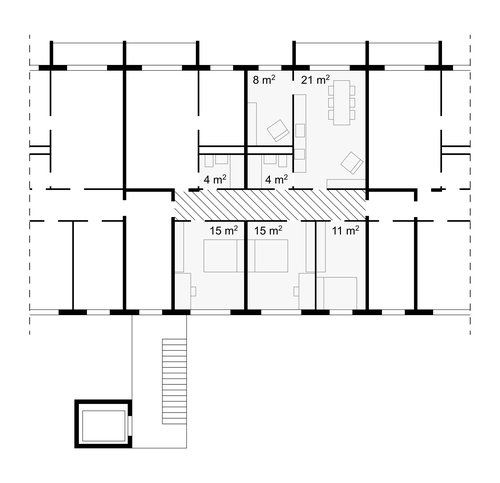

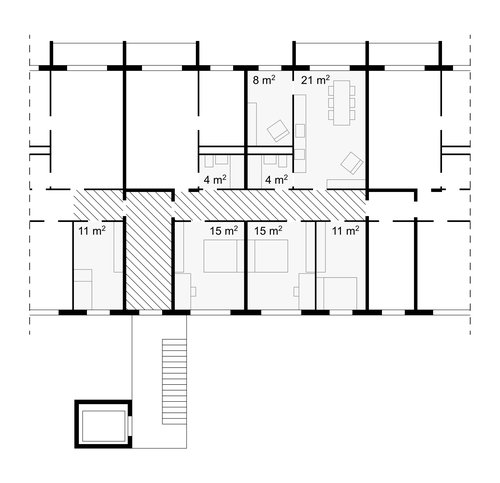

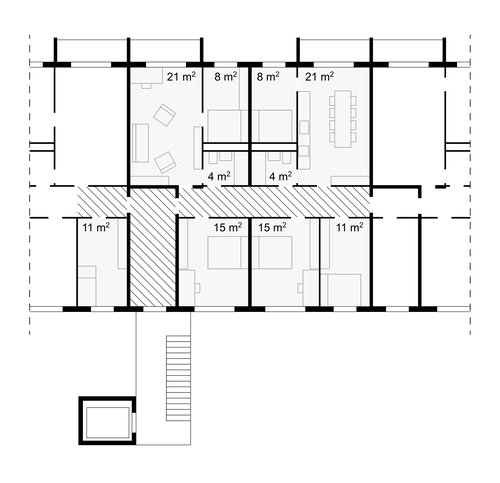

The six-story residential buildings of the WBS70 type on Liliensteinstraße in Leipzig’s Grünau district are typical examples of this era of construction in the former GDR. Organized as two-unit structures and owned by a cooperative, the buildings primarily contain two- to three-room apartments. Only the ground floor includes one one-room apartment per basic module, each of which allows access from both sides. The consistent modular design produces a highly repetitive structure with only minor differences between the building ends and across buildings. Originally designed for families, the apartments are small: when fully occupied, they offer only around 20–25 m² of living space per person. Today, several factors – including demographic shifts among the resident population, the district’s peripheral location, the lack of (programmatic) flexibility, and the near-complete absence of small one-room units – have led to an increased risk of underoccupancy.

However, the very space-efficient floor plans mean that even when underoccupied, the per-person space consumption remains relatively low. The goal of the intervention is therefore not only to reduce per capita space consumption but especially to increase the appeal of the buildings to a wider range of tenant groups, household types, and community configurations. The transformation begins with the main access routes. New, externally mounted access towers will replace up to three of the existing stairwells. They will provide full accessibility to all apartments and require no further intervention in the existing structure, which is already stretched to its limits in terms of structural integrity and fire protection. These new towers can be positioned either where the original stairwells stood or at the closed front ends of the buildings. The removed staircases will free up additional space that can be converted into shared and flexible-use rooms or informal vertical secondary access routes within the building. These measures enable the size of potential sub-communities to be varied and constantly adapted over time – even across multiple floors.

Because the structure has no static reserves and many elements were built using outdated, highly pragmatic methods shaped by material shortages at the time, any structural intervention should be kept to a minimum. [21] This applies in particular to new door openings in the load-bearing apartment and building partition walls (15 cm thick, mostly unreinforced precast concrete), which are now used to connect the apartment corridors into a potential large, continuous (living) corridor spanning the length of the building. By contrast, shifting doors in the non-load-bearing walls between living rooms and former kitchens, as well as adding an extra door to the bathroom, appears proportionate and significantly enhances how residents can use their units individually. It should also be explored whether, as part of the necessary reinforcement of the 6 cm-thick, non-load-bearing concrete walls between rooms and corridors, additional windows or openings might allow for new spatial reinterpretations and improved lighting of the corridor – without compromising the privacy of the individual units. [22]

While the transformation of existing floor plans initially appears straightforward, its practical implementation raises significant questions and encounters potentially prohibitive challenges. These questions span several critical areas:

- Economic Feasibility and Ownership Structures

Ownership structures, alongside associated participation and decision-making processes, as well as obligations from funding models, must be carefully analyzed and integrated into the planning. In certain cases, these factors can make interventions that are technically and structurally straightforward seem practically unfeasible. The economic, temporal, and procedural feasibility of modifications in existing buildings must also be considered. Intervention strategies may need to be specifically tailored or adapted to address these constraints. - Technical and Building Systems Challenges (Decentralization)

The structural characteristics of the buildings in question require the development or application of bespoke technical solutions. These challenges vary depending on the era of construction. For instance, modifications might necessitate the removal of underfloor heating systems, among other adjustments. Due to their operational flexibility, the new floor plans may impose additional demands on building services. For example, what impact will the desired flexibility have on water, wastewater, and electrical systems? Additionally, what role could currently experimental solutions, such as dry toilets and recirculating showers, play? Similarly, smart home technologies, often associated with high-end real estate, could be relevant. The proposed transformations also place heightened demands on building components like doors. particularly regarding their reusability or upgrading in line with sustainability objectives. [23] - Sociological Aspects

These transformations also raise new questions in fields like social science, housing sociology, and housing psychology. While these topics have not yet been explored in depth by the authors, they are crucial for successful implementation and should be incorporated into future planning efforts.

Given the complexity and variety of factors influencing implementation, the authors propose advancing to the next project phase. This phase should prioritize concrete planning investigations over schematic approaches, enabling a closer examination of project-specific constraints and the development of tailored solutions. The ultimate goal should not be to gather singular experiences and insights for a one-time application, but rather to use specific cases to create a demonstrator – a real-world test environment. Such a demonstrator would facilitate systematic testing, measurement, and observation, providing insights that could, ideally, be at least partially transferable to other projects and contexts. [24]

Teaser, 1–73: Almannai, R., Fischer, F., & Wagner, Y.

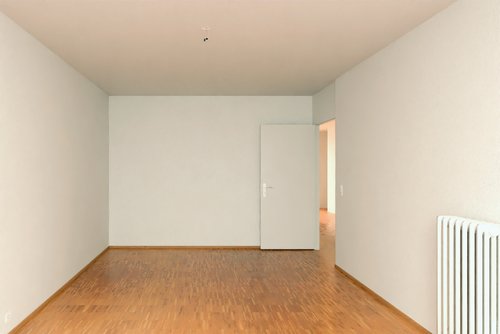

6–9, 22–23, 34–37, 48–49, 60–61: The visualisations are based on a reproduction of existing photographs of the projects using 3D models and blender renderings. In the case of the Parkkolonnaden project in Berlin by Diener & Diener Architekten no original images of the living spaces were available. These were fictitiously (re)constructed according to the architects' material and detail standards at the time the project was created. The authors would like to thank the architect Florian Kessel, Berlin, for his advice and suggestions.

The architectural expression of all conversions was generated by using a camouflage technique in the style of the existing building, the handwriting of the respective architects and the period of origin. In the case of the Goldacker project, which has a new construction component due to the idea of an extension layer, the current Zurich zeitgeist was used for the aesthetic expression in order to avoid any specific design intentions of the authors of this paper. The aesthetic approach in this project borrows directly elements and colours from Lütjens Padmanabhan Architects. The work of this firm has become the dominant blueprint for the designs and design elements of an entire generation of architects over the past ten years.

The term 'Bauwende' has been used in German-speaking countries for several years to describe the substantial changes required in the construction industry to address climate protection. While terms like 'building revolution' or 'construction slowdown' might better capture the scale of transformation, 'Bauwende' has been deliberately adopted for its positive connotations. This term has become a consensus choice, adopted by professional associations, the media, the construction industry, and even politicians, such as the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR) within Germany’s Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community. Drawing on a traditional narrative of progress, "Bauwende" not only evokes the political transformation of 1989 but also references Konrad Wachsmann’s seminal 1959 work, "Wendepunkte im Bauen" ("Turning Points in Construction"). Ironically, the very faith in progress and the industrialization of building that Wachsmann advocated could be seen as contributing factors to the current challenges facing the construction sector.

The initial sizes of the living spaces should be carefully evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Almannai, R., Fischer, F., & Wagner, Y. (2025). Nucleus living—The Basics, Experiences, Outlook. RWTH Aachen, Chair of Housing and Design Basics. wohnbau.site/nucleus-living

In Switzerland, approximately 5,000 buildings are demolished each year. In Germany, about 5,900 residential buildings and 9,000 non-residential buildings are demolished annually. The construction industry in Switzerland accounts for 84% of the country’s waste and roughly one-third of its greenhouse gas emissions. (By comparison, the construction industry in Germany is responsible for 54% of the nation’s total waste.) Statista Research Department. (2023). Abriss von Wohngebäuden in Deutschland nach Gebäudeart in den Jahren 2002 bis 2022. Statista. https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/198175/umfrage/abriss-von-wohngebaeuden-in-deutschland-seit-2002-nach-wohnungsanzahl

The older a building, the easier it is to recover reusable materials and components. In contrast, newer buildings present challenges due to their construction methods. Gurtner & Starovicova, 2023. Wiederverwendung in der schweizerischen Bauindustrie: Potentiale, Herausforderungen und Ansatzpunkte. Berner Fachhochschule. P. 19. https://arbor.bfh.ch/20190/

The disproportion between newly created living space and the number of flats or residents is illustrated by the example of the city of Zurich, where the issue of new replacement construction is particularly relevant: Rey, U. (2011). Bauliche Verdichtung durch Ersatzneubau in der Stadt Zürich. Stadtentwicklung Zürich. https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch/content/dam/misc/de/mitteilungsarchiv/2011/10/110727_Ersatzneubau_STEZ_zur_Publikation.pdf

A recent evaluation in the city of Zurich reveals that new flats directly contribute to the displacement of vulnerable populations: Kaufmann, D., Lutz, E., Kauer, F., Wehr, M., & Wicki, M. (2023). Erkenntnisse zum aktuellen Wohnungsnotstand: Bautätigkeit, Verdrängung und Akzeptanz. ETH Zurich. P. 7-14. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11850/603229

The living space of a three-room flat in Zurich's Goldacker housing development, designed by Karl Egender in 1947 and now slated for demolition as part of the city's replacement construction practices, is approximately 62 sqm. By contrast, the average living space of a three-room flat in the Canton of Zurich in 2023 is 80.8 sqm: Bundesamt für Statistik BFS. (2024). Durchschnittliche Wohnfläche nach Zimmerzahl und Kanton. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/kataloge-datenbanken.assetdetail.32329626.html

For a detailed explanation of invisible living space and strategies for utilizing it, see: Fuhrhop, D. (2023). Der unsichtbare Wohnraum: Wohnsuffizienz als Antwort auf Wohnraummangel, Klimakrise und Einsamkeit. transcript.

For information on the percentage of underoccupied flats in Germany (35%), see: Zimmermann, P., Brischke, L.-A., Bierwirth, A., & Buschka, M. (2022). Unterstützung von Suffizienzansätzen im Gebäudebereich (No. 09/2023; BBSR-Online-Publikation). Hochschule Luzern – Technik & Architektur Institut für Architektur (IAR). P. 24-25. https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/veroeffentlichungen/bbsr-online/2023/bbsr-online-09-2023.html

A detailed discussion on the importance of flexibility and its impact on housing forms can be found in: Almannai, R., Fischer, F., & Wagner, Y. (2025). Nucleus living—The Basics, Experiences, Outlook. RWTH Aachen, Chair of Housing and Design Basics. wohnbau.site/nucleus-living

Cf. ibid.

The question arises whether, from a sociological perspective, exchanging an flat within the same building truly equates to exchanging something of equal value. See: Hasse, J. (2020). Wohnungswechsel: Phänomenologie des Ein- und Auswohnens. Transcript. P. 40-48.

Under-occupancy is identified when the number of residents in an flat is below the number of rooms minus 2, while over-occupancy occurs when the number of residents exceeds the number of rooms plus 2. [...] Should inappropriate occupancy persist for seven years, the management offers three relocation options. Refusal of a third offer may lead to exclusion from the cooperative and termination of the tenancy. Rental regulations of the Sonnengarten Building Cooperative Zurich. (2018, July). https://bg-sonnengarten.ch/sites/default/files/dateien-publikationen/2018.07.01%20Vermietungsreglement.pdf

In Switzerland, "gray rooms" refer to spaces not essential for household use, often used for storage or activities that could be relocated to shared spaces (e.g., hobby or exercise rooms). This term, while not technically established, is comparable to "invisible living space" as used by Daniel Führhop. See footnote 9. See also: https://gwg.ch/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/GWG_Jahresbericht_2019_A4_einzel.pdf.

Examples of the mix of different flat sizes within the same building, along with a more detailed explanation, can be found in: Geist, J. F., & Kürvers, K. (1984). Das Berliner Mietshaus 1862-1945. Prestel. P. 227.

For statistics on the percentage of people living in under-occupied dwellings, see: Statista Research Department. (2024). Anteil der Bevölkerung in Deutschland, der in unterbelegten Wohnungen lebt, von 2005 bis 2023 nach Verstädterungsgrad. Statista. https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1405151/umfrage/anteil-von-personen-in-unterbelegten-wohnungen-in-deutschland-nach-verstaedterungsgrad/

In the area of the central bathrooms, the passage width of the corridor is approx. 75 cm, which is well below current conventional corridor widths, and in the area of the stairwells, at only 1.00 m, it is also below current conventional corridor widths and, accordingly, well below the minimum movement radius for a barrier-free environment. (The relevant areas are marked with a lightning bolt or arrow symbol on the floor plan).

However, a potential conflict of objectives with issues of accessibility and/or inclusion would be inevitable in this case.

In this specific case, photographic evidence suggests the absence of underfloor heating and controlled ventilation. Instead, the rooms appear to feature wall-mounted tube radiators.

A feasibility study provides more detailed information in this regard:

Almannai, R., Fischer, F., Wagner, Y., Saat, R., Vollbracht, N., & Helten, M. (2025). Nukleuswohnen im Bestand, Machbarkeitsstudie Liliensteinstrasse 17–39. RWTH Aachen, Chair of Housing and Design Basics und Reem Almannai.

See also: Allisat, G. (1997). Leitfaden für die Instandsetzung und Modernisierung von Wohngebäuden in der Plattenbauweise, Wohnungsbauserie 70—WBS 70 6,3 t. Institut für Erhaltung und Modemisierung von Bauwerken e.V. an der TU Berlin.

Planning is currently underway for a nucleus demonstrator, including the possibility of multi-week test living and proposed research on various topics (circulation spaces, apartment openness, new relationship forms and living arrangements, acoustic conditions, multivalued doors, role of bathrooms). In this project, up to eight existing residential units across two floors are to be temporarily transformed into nucleus living with up to 12 flexible-use rooms. Authors: Almannai, R., Fischer, F., Wagner, Y., Saat, R., Vollbracht, N., & Helten, M. (2024–26).

A detailed examination of the requirements and retrofitting options for the door component can be found in: Almannai, R., Fischer, F., & Wagner, Y. (2025). The Door—A sketch of the refurbishment of existing doors in residential buildings using exemplary door systems from three eras. RWTH Aachen, Chair of Housing and Design Basics. (In progress)

In 2024, the authors, in collaboration with HOWOGE (Berlin), Deutsches Jugendinstitut e.V. (Munich), and Genossenschaft Lipsia (Leipzig), submitted a research proposal titled “Nucleus Housing in Existing Buildings” to address this objective.

The term 'Bauwende' has been used in German-speaking countries for several years to describe the substantial changes required in the construction industry to address climate protection. While terms like 'building revolution' or 'construction slowdown' might better capture the scale of transformation, 'Bauwende' has been deliberately adopted for its positive connotations. This term has become a consensus choice, adopted by professional associations, the media, the construction industry, and even politicians, such as the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR) within Germany’s Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community. Drawing on a traditional narrative of progress, "Bauwende" not only evokes the political transformation of 1989 but also references Konrad Wachsmann’s seminal 1959 work, "Wendepunkte im Bauen" ("Turning Points in Construction"). Ironically, the very faith in progress and the industrialization of building that Wachsmann advocated could be seen as contributing factors to the current challenges facing the construction sector.

The initial sizes of the living spaces should be carefully evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Almannai, R., Fischer, F., & Wagner, Y. (2025). Nucleus living—The Basics, Experiences, Outlook. RWTH Aachen, Chair of Housing and Design Basics. wohnbau.site/nucleus-living

In Switzerland, approximately 5,000 buildings are demolished each year. In Germany, about 5,900 residential buildings and 9,000 non-residential buildings are demolished annually. The construction industry in Switzerland accounts for 84% of the country’s waste and roughly one-third of its greenhouse gas emissions. (By comparison, the construction industry in Germany is responsible for 54% of the nation’s total waste.) Statista Research Department. (2023). Abriss von Wohngebäuden in Deutschland nach Gebäudeart in den Jahren 2002 bis 2022. Statista. https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/198175/umfrage/abriss-von-wohngebaeuden-in-deutschland-seit-2002-nach-wohnungsanzahl

The older a building, the easier it is to recover reusable materials and components. In contrast, newer buildings present challenges due to their construction methods. Gurtner & Starovicova, 2023. Wiederverwendung in der schweizerischen Bauindustrie: Potentiale, Herausforderungen und Ansatzpunkte. Berner Fachhochschule. P. 19. https://arbor.bfh.ch/20190/

The disproportion between newly created living space and the number of flats or residents is illustrated by the example of the city of Zurich, where the issue of new replacement construction is particularly relevant: Rey, U. (2011). Bauliche Verdichtung durch Ersatzneubau in der Stadt Zürich. Stadtentwicklung Zürich. https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch/content/dam/misc/de/mitteilungsarchiv/2011/10/110727_Ersatzneubau_STEZ_zur_Publikation.pdf

A recent evaluation in the city of Zurich reveals that new flats directly contribute to the displacement of vulnerable populations: Kaufmann, D., Lutz, E., Kauer, F., Wehr, M., & Wicki, M. (2023). Erkenntnisse zum aktuellen Wohnungsnotstand: Bautätigkeit, Verdrängung und Akzeptanz. ETH Zurich. P. 7-14. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11850/603229

The living space of a three-room flat in Zurich's Goldacker housing development, designed by Karl Egender in 1947 and now slated for demolition as part of the city's replacement construction practices, is approximately 62 sqm. By contrast, the average living space of a three-room flat in the Canton of Zurich in 2023 is 80.8 sqm: Bundesamt für Statistik BFS. (2024). Durchschnittliche Wohnfläche nach Zimmerzahl und Kanton. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/kataloge-datenbanken.assetdetail.32329626.html

For a detailed explanation of invisible living space and strategies for utilizing it, see: Fuhrhop, D. (2023). Der unsichtbare Wohnraum: Wohnsuffizienz als Antwort auf Wohnraummangel, Klimakrise und Einsamkeit. transcript.

For information on the percentage of underoccupied flats in Germany (35%), see: Zimmermann, P., Brischke, L.-A., Bierwirth, A., & Buschka, M. (2022). Unterstützung von Suffizienzansätzen im Gebäudebereich (No. 09/2023; BBSR-Online-Publikation). Hochschule Luzern – Technik & Architektur Institut für Architektur (IAR). P. 24-25. https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/veroeffentlichungen/bbsr-online/2023/bbsr-online-09-2023.html

A detailed discussion on the importance of flexibility and its impact on housing forms can be found in: Almannai, R., Fischer, F., & Wagner, Y. (2025). Nucleus living—The Basics, Experiences, Outlook. RWTH Aachen, Chair of Housing and Design Basics. wohnbau.site/nucleus-living

Cf. ibid.

The question arises whether, from a sociological perspective, exchanging an flat within the same building truly equates to exchanging something of equal value. See: Hasse, J. (2020). Wohnungswechsel: Phänomenologie des Ein- und Auswohnens. Transcript. P. 40-48.

Under-occupancy is identified when the number of residents in an flat is below the number of rooms minus 2, while over-occupancy occurs when the number of residents exceeds the number of rooms plus 2. [...] Should inappropriate occupancy persist for seven years, the management offers three relocation options. Refusal of a third offer may lead to exclusion from the cooperative and termination of the tenancy. Rental regulations of the Sonnengarten Building Cooperative Zurich. (2018, July). https://bg-sonnengarten.ch/sites/default/files/dateien-publikationen/2018.07.01%20Vermietungsreglement.pdf

In Switzerland, "gray rooms" refer to spaces not essential for household use, often used for storage or activities that could be relocated to shared spaces (e.g., hobby or exercise rooms). This term, while not technically established, is comparable to "invisible living space" as used by Daniel Führhop. See footnote 9. See also: https://gwg.ch/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/GWG_Jahresbericht_2019_A4_einzel.pdf.

Examples of the mix of different flat sizes within the same building, along with a more detailed explanation, can be found in: Geist, J. F., & Kürvers, K. (1984). Das Berliner Mietshaus 1862-1945. Prestel. P. 227.

For statistics on the percentage of people living in under-occupied dwellings, see: Statista Research Department. (2024). Anteil der Bevölkerung in Deutschland, der in unterbelegten Wohnungen lebt, von 2005 bis 2023 nach Verstädterungsgrad. Statista. https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1405151/umfrage/anteil-von-personen-in-unterbelegten-wohnungen-in-deutschland-nach-verstaedterungsgrad/

In the area of the central bathrooms, the passage width of the corridor is approx. 75 cm, which is well below current conventional corridor widths, and in the area of the stairwells, at only 1.00 m, it is also below current conventional corridor widths and, accordingly, well below the minimum movement radius for a barrier-free environment. (The relevant areas are marked with a lightning bolt or arrow symbol on the floor plan).

However, a potential conflict of objectives with issues of accessibility and/or inclusion would be inevitable in this case.

In this specific case, photographic evidence suggests the absence of underfloor heating and controlled ventilation. Instead, the rooms appear to feature wall-mounted tube radiators.

A feasibility study provides more detailed information in this regard:

Almannai, R., Fischer, F., Wagner, Y., Saat, R., Vollbracht, N., & Helten, M. (2025). Nukleuswohnen im Bestand, Machbarkeitsstudie Liliensteinstrasse 17–39. RWTH Aachen, Chair of Housing and Design Basics und Reem Almannai.

See also: Allisat, G. (1997). Leitfaden für die Instandsetzung und Modernisierung von Wohngebäuden in der Plattenbauweise, Wohnungsbauserie 70—WBS 70 6,3 t. Institut für Erhaltung und Modemisierung von Bauwerken e.V. an der TU Berlin.

Planning is currently underway for a nucleus demonstrator, including the possibility of multi-week test living and proposed research on various topics (circulation spaces, apartment openness, new relationship forms and living arrangements, acoustic conditions, multivalued doors, role of bathrooms). In this project, up to eight existing residential units across two floors are to be temporarily transformed into nucleus living with up to 12 flexible-use rooms. Authors: Almannai, R., Fischer, F., Wagner, Y., Saat, R., Vollbracht, N., & Helten, M. (2024–26).

A detailed examination of the requirements and retrofitting options for the door component can be found in: Almannai, R., Fischer, F., & Wagner, Y. (2025). The Door—A sketch of the refurbishment of existing doors in residential buildings using exemplary door systems from three eras. RWTH Aachen, Chair of Housing and Design Basics. (In progress)

In 2024, the authors, in collaboration with HOWOGE (Berlin), Deutsches Jugendinstitut e.V. (Munich), and Genossenschaft Lipsia (Leipzig), submitted a research proposal titled “Nucleus Housing in Existing Buildings” to address this objective.